Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Reflection on and result of the first cycle

المؤلف:

Nona Muldoon & Chrisann Lee

المصدر:

Enhancing Teaching and Learning through Assessment

الجزء والصفحة:

P103-C10

2025-06-18

351

Reflection on and result of the first cycle

The learning design strategically embedded formative assessment in the tutorial activities and, in allowing the students to work in groups, which often included producing learning artifacts, they were able to demonstrate what they know through interactive class presentations. Group activities, according to James and McInnis (2001, p.10) 'mimic the approaches to problem-solving found in the workplace'. Hence, group work also provided opportunities for situating learning in a realistic way. The learning environment indeed provided a rich context within which students could take initiative in formative assessment, which consequently provided opportunities for students to engage with the learning of accounting concepts in a deep and meaningful way. In this learning design, formative assessment is built into the teaching and learning of a particular topic where students are likely to appreciate that it is part of the normal effort of learning about that topic. As Isaacs (2001) suggests, assessment that is added onto the subject is likely to be resented by students as it can be seen as an imposition and can appear somewhat superfluous. 'Assessment is therefore an integral component of the teaching and learning process rather than an appendix to it' (James & McInnis, 2001, p.4).

The collaborative learning environment indeed became a motivation for students to participate fully in formative assessment and thus enhanced their interest and learning in the subject. The tutor was then empowered to evaluate students' level of understanding and provide ongoing feedback on their progress. More importantly, such an approach provided a means to clarify any problematic concepts and take corrective measures in a timely manner. Viewed in this way, formative assessment had a profound impact on improving student learning. The intent was developmental, focusing on helping students to progress in the subject, rather than on assigning grades (James & McInnis, 2001; Ritter & Wilson, 2001).

It is a common perception of some academics (especially early career academics) that students may not participate actively in learning activities if such activities are not graded. They are of the view that the requirements of formal assessment often drive the learning strategy adopted by students (see for example discussions in Gow, et. al., 1994; Hand et. al., 1996). Akin to the management saying that "what gets measured get managed", in education it seems that what gets assessed gets learned particularly if the task contributes to the final grade. However, results in this first cycle of the research show that students will participate in ungraded assessment provided they are given current, meaningful and enjoyable learning activities. As the following typical student One-minute feedback indicates:

“Hey it is fun, relaxed and enjoyable! And you learn stuff at the same time!”

“I like the way we do group activities and you really explain everything until we understand. Everything is mostly clear to me.”

“Very well organized. All explanations are very clear. I did enjoy and get a lot out of the group work that we did.”

“What really helps is going through the tutorial homework at the tutorial and explaining it. Having discussion of accounting concept is great. I like how you ask us questions so it makes us think.”

“After each tutorial I understand a lot more. There was not anything that I did not understand today. I really like class activities and presenting our ideas to the class.”

“I actually enjoy this class; you make it easy to understand because you are approachable. Thanks!”

“Classes are more active, no real problems. More depth to questions is good. Enjoying accounting finally.”

A customized survey was also conducted in the final teaching week of the semester. The survey aimed to evaluate the tutor's teaching in terms of promoting active and deep approaches to learning, encouraging student participation, and generic skills development. There were 15 questions in the survey, with 21 respondents from a population of two tutorial classes totaling 30 students, yielding a response rate of 70%1.

The responses were mainly from those students who had consistent attendance over the semester and those who attended the final tutorial session. The results of the student survey were consistent with the feedback from the one-minute papers, and indicated that the tutor had clearly explained concepts (mean 6.23, range 0-7); stimulated students to think and feel involved in the classes (mean 6.23); encouraged students to express their views on the topic (mean 6.05); motivated students to think critically (mean 6.0) and, in general, appeared enthusiastic in her teaching (mean 6.76).

The analysis of the outcomes of these action-oriented TLAs validated what Ramsden (2003) suggests that the role of the teacher is not about transmission of information but making learning possible. This is achieved by creating a learning context for students to construct meanings and discover knowledge for themselves. Indeed, the experience from this first cycle indicates that when academic teachers demonstrate enthusiasm, passion for the discipline and have the ability to provide moral and behavioral support, students respond positively even to ungraded assessment.

However, the student who commented "Enjoying accounting finally" subsequently failed the subject. This particular student demonstrated through formative assessment an improved level of critical-thinking and problem-solving skills when applying accounting concepts. So why did this student fail in the examination despite enjoying accounting and doing the work? The student provided feedback that he wasn't used to memorising information and preferred the types of testing used in formative assessment. This triggered the authors to look at the design and deployment of the curriculum. While there were certainly many factors that contributed to the failure, one of the reasons was that there was a 'misalignment' between components in the curriculum. The final examination which formed part of summative assessment predominantly focused on testing declarative knowledge, such as procedures and facts recall. Declarative knowledge is knowledge that one can declare, for example tell somebody about what they read in the textbook or give a definition of something (Biggs, 2003). In contrast, the TLAs including formative assessment in the tutorials focused less on the development of declarative knowledge.

With the benefit of hindsight, the tutor overlooked to consider the format of the final exam while designing learning activities and failed to highlight the importance of mastering accounting concepts for the purpose of the exam, e.g. learning the definitions of terms. In fact, there was no consideration on the part of the tutor on how students will be assessed in the final exam. The tutor's teaching goal was to provide a motivational context within which students can construct knowledge of content through the use of problem cases, rather than relying on memory and recalling of facts. The approaches used focused largely on problem cases, and while the authentic nature of learning activities and formative assessment that were used in the tutorials allowed for declarative knowledge to turn into functioning knowledge (Biggs, 2003), it failed to align with the content of the exam and vice versa. The content of the final examination consisted of thirty multiple choice questions and four written questions typically asking students to journalize transactions or prepare adjusting entries.

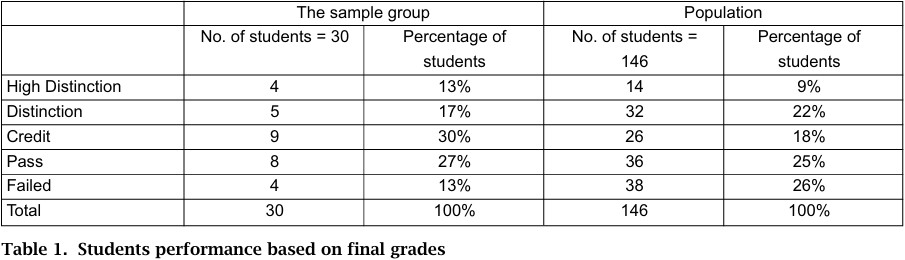

It is worth noting that there was no formal analysis carried out on the impact of the misalignment on the success or failure in the final examination of the two tutorial groups. However, of the 30 students in these two groups, four were awarded High Distinction, five Distinction, nine Credit, eight Pass grades and four Fail grades. The results in Table 1 show the performance of students in the sample group based on final grades compared to the rest of the population. There were nine tutorial groups in total.

Despite the misalignments in the teaching strategy, the students in the two tutorial groups performed reasonably well in the subject overall. As observed during formative assessment, the collaborative learning environment for these two tutorial groups facilitated students' motivation and willingness to engage in higher level thinking. The final grades indicate that over half of the students in the sample group achieved above satisfactory performance, which may suggest that teaching strategies that facilitate deeper approaches to learning are preferable to surface approaches in achieving quality student learning outcomes (Ramsden, 2003; Prosser & Trigwell, 1999). However, this is an area that the authors recognized needs further study to take into account many other variables.

Given that the aim of higher education is to develop functioning knowledge, i.e. the integration of knowledge base (declarative knowledge), skills required for the profession (procedural knowledge) and the context for using them to solve problems (conditional knowledge) (Biggs, 2003), it may be useful to also examine assessment practices in first year accounting more closely to identify if they are constructively aligned with other components of the curriculum.

1Due to re-analysis, there is a variation in the data from previously published results in Lee, C. (2005), Strategies for promoting active learning in tutorials: Insights gained from a first-year accounting subject. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Innovation in Accounting Teaching and Learning, University of Tasmania, Australia.

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)