Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Extension

المؤلف:

Bernd Heine and Tania Kuteva

المصدر:

The Genesis of Grammar

الجزء والصفحة:

P35-C1

2026-02-21

56

Extension

Of all the parameters, extension is the most complex, for two reasons. First, it has a sociolinguistic, a text-pragmatic, and a semantic component. The sociolinguistic component concerns the fact that grammaticalization starts with innovation (or activation) as an individual act, whereby some speaker (or a small group of speakers) proposes a new use for an existing form or construction, which is subsequently adopted by other speakers, ideally diffusing throughout an entire speech community (propagation; see e.g. Croft 2000: 4–5). The text-pragmatic component involves the extension from a usual context to a new context or set of contexts, and the gradual spread to more general paradigms of contexts (for an example of the dramatic effects that this process may have, see “The present approach”). The semantic component finally leads from an existing meaning to another meaning that is evoked or supported by the new context. Thus, text pragmatic and semantic extension are Janusian sides of one and the same general process characterizing the emergence of new grammatical structures.

Second, the term extension has been used in a variety of different ways and in different frameworks. The most relevant use of it as a technical term is that by Harris and Campbell (1995), who refer to it as what they consider to be one of the three basic mechanisms of syntactic change.1 In their model, extension has the effect that a condition on an existing rule is removed. While this use differs in a number of respects from ours, there is considerable overlap, as is suggested by the examples given by these authors, some of which also satisfy our criteria of extension. What distinguishes the two mainly is, first, that in our model extension is framed in terms of pragmatic notions rather than of syntactic rules, second, that we restrict the term to changes where a given linguistic expression acquires new contexts of use while Harris and Campbell use extension in a more general sense, and third, we argue that extension entails some change in meaning, however minute this change may be (see under semantic generalization below), while meaning does not play a central role in Harris and Campbell’s model.

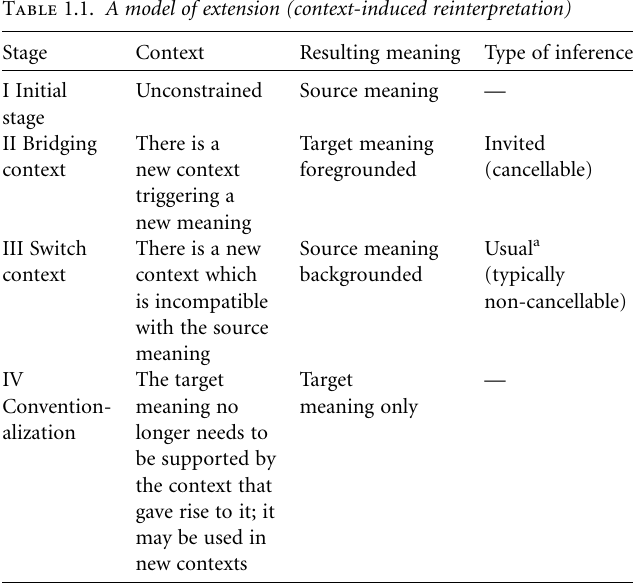

A number of approaches have been used to deal with the phenomena relating to extension (see e.g. Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Traugott and Dasher 2002: 34–9); in the present work we will use the four-stage model of context-induced reinterpretation depicted in Table 1.1 to describe the most salient characteristics of extension (see Heine 2002b for more details).

Table 1.1 suggests that the transition from a less grammatical (e.g. lexical) meaning of stage I to a more grammatical meaning of stage IV does not proceed directly; rather, it involves two intermediate stages, viz. stages II and III. A central question that arises is the following: What is the factor that is responsible for a new context triggering a new meaning (stage II) or backgrounds an existing meaning (stage III)? Available research findings suggest that there are two possible factors: (a) semantic generalization, whereby new contexts entail a more general meaning, and (b) invited inferencing, in that new contexts suggest new meanings.

Semantic generalization is the one most generally involved (Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994). We may illustrate this with the following example. In (14a), the item in serves its canonical function as a spatial preposition, and much the same applies to (14b). But when in is extended to contexts such as (14c),2 its meaning can no longer be reduced to that of a spatial preposition, that is, it has become more general—in other words, the more contexts of use a linguistic expression acquires, the more it tends to lose in semantic specificity and to undergo semantic generalization (that is, desemanticization; see below). Thus, semantic generalization (or bleaching) is an obligatory consequence of extension, and Haspelmath (1999a: 1062) goes so far as to argue that semantic generalization is in a sense the cause of the other processes of grammaticalization.

a The term ‘‘usual’’ inference is adopted from Paul ([1880] 1920). Hopper and Traugott (2003: 80–1) use the term conventional implicature instead. We prefer not to refer to this inference as ‘‘conventional’’ since it is entirely dependent on the context and, hence, not conventionalized to the extent that it constitutes an independent grammatical meaning (see stage IV).

(14) English

a. John died in London.

b. John died in Iraq.

c. John died in a car accident.

Invited inferencing is less general as a factor, even if it is involved in many instances of grammaticalization (see Traugott and Dasher 2002: 34–40).

It has the effect that, due to a specific context, a new meaning is foregrounded (stage II), even if it is still cancellable. But it may happen that the invited inference turns into a usual one in specific contexts—with the effect that the old meaning is backgrounded (stage III). Example (14) can illustrate this factor: In (14a), the item in serves its canonical function as a spatial preposition. This also applies to (14b), but on account of encyclopaedic (world) knowledge, in this case of contemporary history, (14b) may trigger an invited inference to the effect that the location expressed by in may have been causally responsible for the event described by the verb—hence a stage-II interpretation is possible. However, this interpretation is always cancellable, in that the speaker may insist that that particular location was not causally responsible for John’s death. In a context like (14c), the causal inference is the usual one, in that an interpretation of in as a spatial or temporal preposition makes little sense—hence that interpretation is backgrounded and the only reasonable meaning of in is a causal one. While it is still theoretically possible to cancel the causal inference, this would be highly unusual.

It has been argued or implied that the main trigger of grammaticalization is frequency of use: The more often a given form or construction occurs, the more likely it is that it will reduce in structure and meaning and assume a grammatical function (Bybee 1985; Diessel 2005: 24; see especially the contributions in Bybee and Hopper 2001). In fact, extension to new (sets of) contexts implies a higher rate of occurrence of the items concerned, and more probable words are more likely to be reduced than less probable ones (cf. the Probabilistic Reduction Hypothesis of Jurafsky et al. 2001). Furthermore, when a grammatical item whose use is optional is used more frequently, its use may become obligatory. Nevertheless, we have found neither compelling evidence to support the hypothesis that frequency is immediately responsible for grammaticalization, nor that grammatical forms are generally used more frequently than their corresponding less grammaticalized cognates.

Two examples may illustrate this. A survey of a larger body of instances of grammaticalization suggests that, overall, non-grammaticalized items that serve as the source of grammaticalization do not necessarily belong to the most frequently used words of a language (see e.g. Heine, Claudi, and Hünnemeyer 1991: 38–9), nor are grammaticalized items necessarily used more frequently than their non-grammaticalized counterparts. The other example is of a different nature: As we saw in “The present approach”, the German verb drohen ‘to threaten’ has given rise to an aspectual-modal auxiliary meaning (‘‘something undesirable is about to happen’’). In Present-Day German, drohen is a main verb in 65.6 percent (173 instances) but an auxiliary only in 34.4 percent (96 instances) of its uses. In a similar fashion, the German verb versprechen ‘to promise’ has been grammaticalized to an aspectual-modal auxiliary (‘‘something desirable is likely to happen soon’’) and, once again, the lexical uses (98.2 percent, 636 instances) clearly outnumber the auxiliary uses (1.8 percent, 12 instances) (Askedal 1997: 17; Heine and Miyashita 2006). To conclude, frequency of use appears to be an epi-phenomenal product of extension rather than being a trigger of it; neither do non-grammaticalized items that serve as the target of grammaticalization necessarily belong to the most frequently used words of a language (see e.g. Heine, Claudi, and Hünnemeyer 1991: 38–9), nor are grammaticalized items necessarily used more frequently than their non-grammaticalized counterparts.

1 The other two mechanisms are reanalysis and borrowing. In more general terms, extension is defined by these authors ‘‘as change in the surface manifestation of a syntactic pattern that does not involve immediate or intrinsic modification of underlying structure’’ (Harris and Campbell 1995: 97). The use of ‘‘reanalysis’’ in the model of these authors overlaps with that of grammaticalization but should not be confused with the latter. In order to avoid confusion, we will not use the term ‘‘reanalysis’’ in this work.

2 These contexts do not exhaust the number of invited inferences associated with in; for example, in the following sentence there is a kind of manner inference (Fritz New-meyer, p.c.): John died in pain.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)