Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Constructive alignment

المؤلف:

Steve Frankland

المصدر:

Enhancing Teaching and Learning through Assessment

الجزء والصفحة:

2025-05-21

139

Constructive alignment

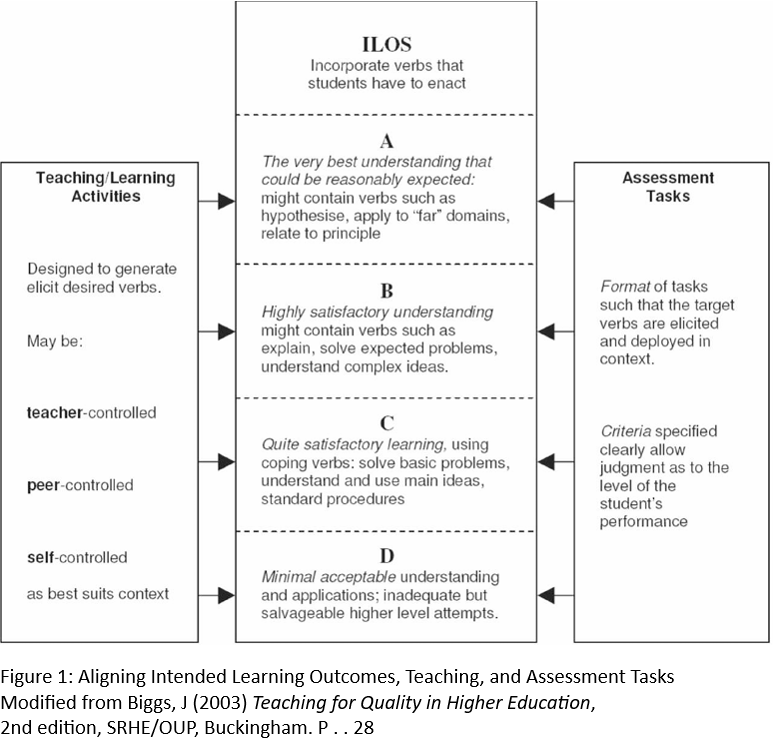

Let me return to my portfolios in 1995. Although they are ostensibly about assessment, they raise questions to do with the design of the whole teaching process. The students had to show that they had met the ILOs: in this case, to show how their knowledge of psychology impacted on their teaching. The assessment tasks they chose were therefore examples of that impact. Assessing required the same activities as did the original learning. Problem-based learning is an excellent example. The ILOs refer to problems to be solved, the teaching method is solving those problems, the assessment is based on how well the problems are solved. There is probably no better way of encouraging students to engage in appropriate learning activities, as Shuell put it, than incorporating these same activities into the assessment tasks.

The crucial verbs or learning activities are therefore contained in:

. the ILOs,

. the teaching method

. the tasks used for assessing if those verbs had been used.

The verbs create alignment throughout the system, and because the alignment is based in constructivist psychology, I call it constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996; 2003) (Figure 1)

It came as no surprise to find that such an obvious idea had been suggested before: fifty years previously, by Ralph Tyler (1949). Tyler’s book was used in most if not all teacher education courses in the USA for years but with zero effect. The time had not yet come. I guess the main problems were, first, the grip measurement model thinking had on education. Norm-referenced assessment, which precluded qualitative assessment in terms of realistic ILOs, had become the conventional wisdom.

Secondly, constructive alignment is hard to put into practice unless different levels of understanding are translated into performances of understanding. What we mean by higher and lower levels of understanding is defined in terms of how students will behave, not just talk. If we stay with declarative knowledge only, students can so easily deceive with ‘cow’, as William Perry (1970) put it, which is playing the academic game by throwing high-sounding terminology around. ‘Bullshit’ is a plainer way of putting it. Perry describes how he gatecrashed a sociology exam at Harvard. He, a non-sociologist, passed easily without having attended a single lecture or having seen the syllabus. This was misalignment on a grand scale—teaching was simply irrelevant—but perfectly explicable on the measurement model of assessment.

Constructive alignment (CA) has in a few years become widely accepted as the way to go in higher education, but the same principles apply in any instructional setting, at any level, including driving instruction. CA is used in the UK and in Hong Kong in the context of quality assurance in university teaching. The Hong Kong PolyU uses it in its assessment guidelines, while the UGC in Hong Kong is supporting two major projects, the Constructive Alignment Project and the Assessment Project itself, which is hosting this Conference.

In the Assessment Project, there are eight subprojects in various departments. Assessment practices have been revised in order to reflect the ILOs in selected subject areas more authentically; they include portfolio assessment, the use of the SOLO taxonomy, self and peer assessment, analysis of online discussion, poster assessment, negotiation between student and supervisor, amongst others.

Some projects are revealing that such changes are hard to implement. Despite the clear signals from the UGC and from institutional mission statements, many departments and teaching staff operate at ground level in the shadow of the measurement model. In one survey conducted in the Assessment Project, a majority of staff saw the main function of assessment as ‘sorting students out’. Assessment tasks are chosen because they are there from time immemorial—since the Han Dynasty in fact—not because the tasks are the most appropriate ones for assessing the content or level of understanding required in the subjects we teach. Using the same assessments tasks whatever the course objectives only result in poor alignment. Students are distracted by the negative backwash, causing them to distort their learning to suit the assessment.

The Assessment Project will hopefully be instrumental in persuading teachers and administrators by example that traditional practice needs turning on its head. If you want to see how, visit the websites of the Project itself, and of the Assessment Resource Centre, where these and many other examples will be displayed. You will see that assessment tasks can be selected to suit how we want students to learn, and criteria established telling us what and how well they have been learned.

That is what assessment is about.

الاكثر قراءة في Assessment

الاكثر قراءة في Assessment

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)