Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

The Teaching Portfolio as a tool to support reflection

المؤلف:

Lorraine Stefani

المصدر:

Enhancing Teaching and Learning through Assessment

الجزء والصفحة:

P120-C12

2025-06-24

37

The Teaching Portfolio as a tool to support reflection

The concept of a Teaching Portfolio is somewhat 'old hat' (e.g. Seldin, 1997; Stefani & Diener, 2005) but there is ample anecdotal evidence of poor uptake and engagement by staff and a low level of meaningful implementation. A project carried out recently at the University of Auckland exploring faculty views on Teaching Portfolios indicated that part of the stumbling block as regards meaningful implementation is that assumptions are made about reflection on teaching as an understood activity (Dobbie et al., 2004). An obvious issue here is that if we ourselves have difficulty conceptualizing and engaging in the processes of reflection on and self-assessing our teaching and classroom practice, how can we really promote reflection on and self-assessment of learning?

There are clear parallels between the concepts of developing and maintaining Teaching Portfolios and the interest in promoting to students the concept of Personal Development Planning (PDP). In the UK in particular there has been considerable emphasis on embedding PDP opportunities within the curriculum. PDP has been described as 'A structured process undertaken by the individual to reflect upon their learning and/or achievement to support personal, educational and career development' (QAAHE, 2005). In an ideal world, students would be enabled to enhance achievement through reflection on current attainment, make strategic decisions based on their strengths and weaknesses and 'evidence' their learning processes.

The parallel processes for staff are: reflecting upon and evaluating the impact their teaching has on student learning, and 'making strategic decisions' relating to their practice (Ramsden, 2003).

There are some excellent examples of Learning Portfolios particularly from Universities in the United States. For example, Alverno College in Milwaukee entitle their portfolio for students: A Diagnostic Digital Portfolio (DDP). This web-based system is designed to enable students to follow their progress throughout their period of study and to process or reflect on the feedback received from faculty, external assessors and peers (Doherty, 2002).

What is interesting about the DDP is that it is embedded within the learning strategy from the outset of the period of study. The emphasis for student learning is on reflection, self-assessment and feedback. The lessons to be gained here relating to a Teaching Portfolio may relate to the issue of feedback. If the only purpose for a Teaching Portfolio is seen to be summative in that it is linked to appraisal systems or extrinsic reward, this may militate against a reflective approach and result in a mechanistic, repository function rather than a developmental, formative function.

Many academic staff struggle with the concept of embedding Personal Development Planning into the curriculum and with articulating to students what it means to self-assess. In a recent book written by Nancy Falchikov on the topic of improving assessment through student involvement (Falchikov, 2005), she presents a definition of self-assessment as follows:

Self-assessment is a way for students to become involved in assessing their own development and learning. She further expands upon this with the following points:

• A way of introducing students to the concept of individual judgement

• Involving students in dialogue with teachers and peers

• Involving individual reflection about what constitutes good work

• Requiring learners to think about what they have learned so far, identifying gaps and ways in which these can be filled and take steps towards remediation (Falchikov, 2005 p.120)

My question to the reader is, what if we were to exchange the word student for 'academic staff member' and make some other minor word changes to the above definition of self-assessment and present this in the context of the purpose of a Teaching Portfolio? Would this support staff in recognizing the parallels between encouraging reflection and self-assessment for students and engaging in self assessment and reflection on their own practice?

In an ideal world teaching and learning would be seen as complementary activities, faculty would take the same scholarly, reflective approach to the facilitation of student learning as they do towards their disciplinary based research. They would also model the processes of reflection for their students - and could do this through the development and maintenance of a Teaching Portfolio.

What lies behind the rhetoric of 'reflective learning' is the consideration of a 'knowledge' and a 'learning' society and the concomitant rise in the importance of intellectual capital (Jary & Parker, 1998). In order to compete effectively in a rapidly changing world, university graduates must be able to adapt their skills to new situations, be able to adapt their knowledge and understanding constantly and be capable of making sound judgements of the value of their own and others' work and to be critical thinkers. It is therefore important that teachers ensure that students understand these objectives and provide them with appropriate guidance and teaching/learning activities to facilitate the achievement of these objectives. If we are to live up to the idea that the teaching function of universities is linked to the presentation and enhancement of Society's intellectual culture (Barnett, 1994), university academics and lecturers must show their understanding of this and accept their role in modelling reflective capacity.

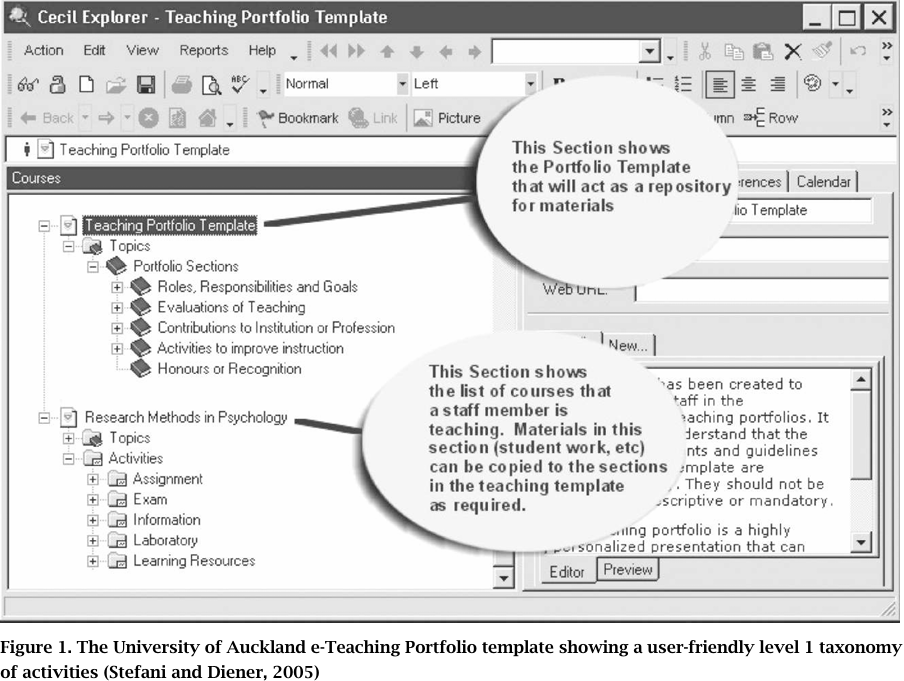

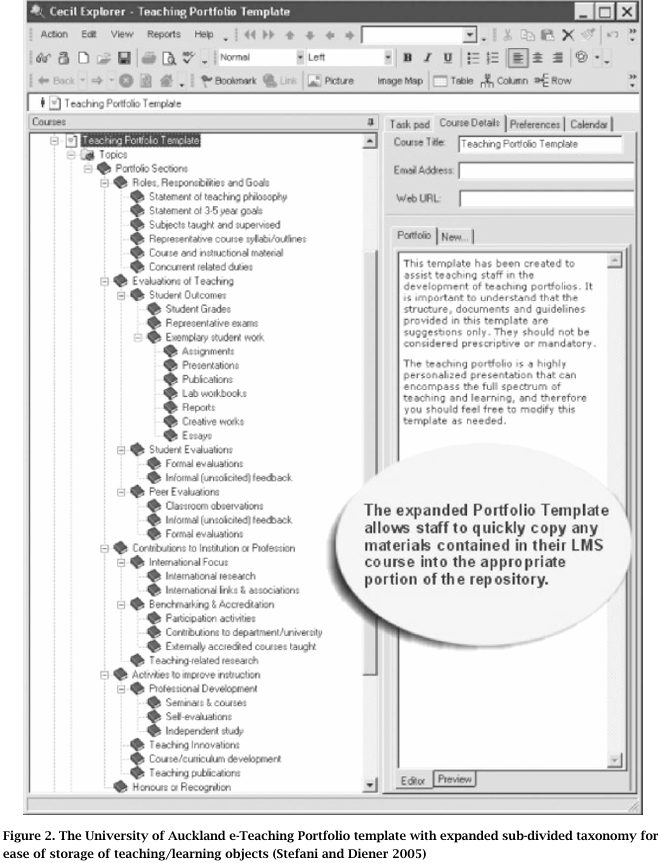

At the University of Auckland a major initiative is underway to raise the profile of Teaching Portfolios. This initiative takes into consideration that the first stage of a Teaching Portfolio is likely to be a matter of developing a user friendly repository structure. On the basis of staff input the model for the portfolio will be based on 5 key aspects of teaching, namely:

• Roles and responsibilities of the individual

• Evaluations of Teaching

• Contributions to Institution or Profession

• Activities to Improve Instruction

• Honour or Recognition

Each of these headings can have a series of sub-headings or sub-files which give guidance as to the sorts of issues which might constitute evidence on current practice. An implicit action in terms of using a repository is reflecting on and recording actions and activities. For example, under Roles and Responsibilities the expectation is that individuals would provide: an indication of particular areas of expertise; the context of their teaching including learning hurdles in the specified discipline; a statement describing roles and responsibilities with a list of courses, student numbers, new course developments, teaching styles and strategies etc.

(While it is not the intention to provide full details on the proposed structure of the Teaching Portfolio, Figures 1 and 2 show the template currently being piloted. Further details of the structure and the supporting Learning Management System can be found

The reflective aspect of the first section of the portfolio would entail a statement on the linkage between the rationale for teaching goals, student learning activities or processes and student outcomes. From this it might reasonably be expected that individuals could draw out a statement on their teaching philosophy, goals and approaches to facilitation of student learning.

If we consider the potential of the portfolio section relating to evaluation of teaching, we must take into account a range of different ways that teaching or classroom practice can be evaluated, judged, assessed. Good teaching involves continuing efforts to evaluate teaching for the purposes of improved learning (Prosser & Trigwell, 2001). In many cases there is an overemphasis on course and lecturer questionnaires with academic staff selecting a raft of questions over which students have no sense of ownership; the questionnaires being distributed too late in a course for any significant changes to be made in response to the outcomes and staff failing to recognize that the students are as much the stakeholder in this process as the staff themselves and thus deserve a 'closing of the loop' in terms of obtaining feedback on the outcomes of this evaluation process. Studies on student evaluations have shown that student evaluation of teaching is related to student achievement as in high achieving students rate their teachers highly (e.g. Marsh, 1987) but rarely does evaluation of this sort draw out parallels between students' conceptions of learning and staff perceptions of teaching (Prosser & Trigwell, 2001). Thus, the conclusion must be drawn that the use of evaluation questionnaires is very limited. As Elton contends, these evaluations are merely an overall measure of satisfaction or dissatisfaction and can only tell us if lecturer A is significantly better or worse than lecturer B (REF). They rarely promote reflection on teaching and learning.

There are other forms of evaluation that can easily be embedded within classroom practice. For example the work of Cross and Angelo on Classroom Assessment Techniques (1994) provides a range of ways in which simple techniques such as the 'Minute Paper' can enable the lecturer to find out what learning is occurring within their lecture session or other teaching and learning setting. One way is to set up very simple questions five minutes before the end of a session such as: 'What were the key things you learned out of today's lecture? and What aspects of today's lecture did you not understand? '. By asking the students to give very brief responses, checking these responses and feeding the outcomes back to these same students at the next encounter, lecturers can find out what learning is occurring, and by having feedback of this type the students themselves can have their learning affirmed or gain a greater insight into their own misunderstandings. Students are confirmed as stakeholders in the evaluation process, staff are enabled to reflect on their classroom practice.

With a user friendly structure for a Teaching Portfolio, it should be a simple process for staff to record the inputs and outputs of classroom evaluation techniques which can be referred to in a future iteration of the particular course.

While it is expected that individuals will be able to draw out from their portfolio evidence of good practice for the purposes of performance review, in parallel with the concept of student learning portfolios such as the Diagnostic Digital portfolio and Personal Development Planning Portfolios, the real potential for enhancement of classroom practice lies in provision of support in the form of formative feedback. It is unlikely that senior staff will have the time and the resource to provide formative feedback on the portfolio - but there are other options, one being the enhancement of peer feedback or peer support strategies as a variation on the concept of peer observation of teaching.

We will explore forms of peer assessment including peer observation of teaching and other potential peer feedback strategies.

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)