Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 10-3-2022

Date: 2023-12-12

Date: 2025-04-19

|

What is Ezafe? (Samiian 1994)

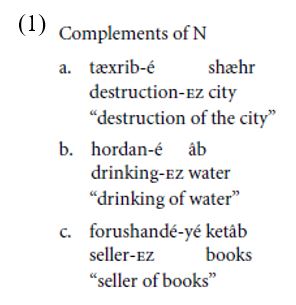

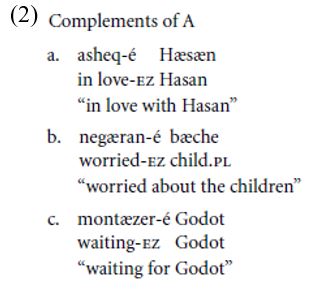

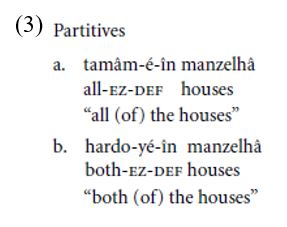

The presence of the Ezafe “linking” morpheme raises a simple and very natural question. What is Ezafe? What function does Ezafe serve in the grammar of Persian and languages like it? In an interesting article, Vida Samiian (1994) argues that Farsi Ezafe is a case marker, inserted before complements of [+N] categories, including Ns, As, and some Ps. Samiian supports this claim by observing that the use of Ezafe extends considerably beyond modification. Many contexts where English would use the (genitive) case-marking preposition of are ones in which Ezafe occurs, including complements of N (1a–c), complements of A (2a–c), and certain partitive constructions (3a, b).

The role played by of in the counterpart English cases is to case-mark the complement following adjectives, nouns, and partitives. Samiian suggests that Ezafe plays the same role here.

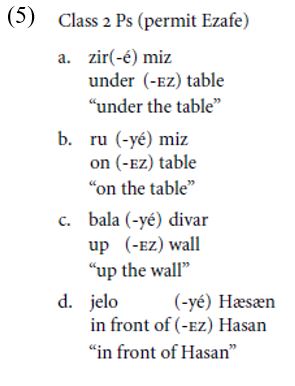

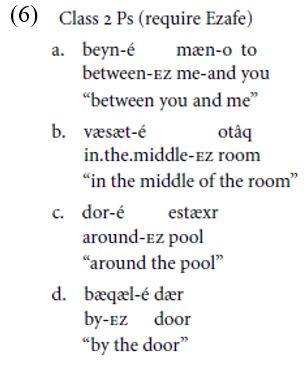

Perhaps the most persuasive piece of evidence Samiian gives is the behavior of the category P, which initially looks like a problem for Samiian’s proposal. Since prepositions are typically analyzed as [−N,−V] elements, PP would not be expected to require Ezafe marking; furthermore, P would not be expected to require Ezafe to case-license its object, contrary to what we observed in (1b)/(3e). However, Samiian shows that the class of prepositions in Farsi is not uniform with respect to Ezafe. As shown in (4), some prepositions reject Ezafe (call these Class 1). By contrast, as shown in (5) and (6), other prepositions either permit Ezafe, or require it (call these Class 2):

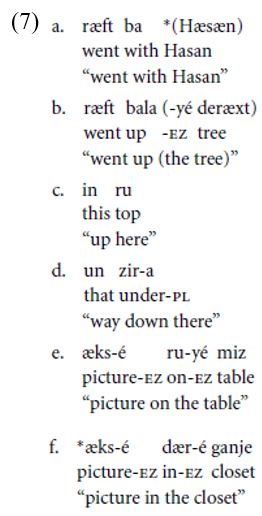

Samiian shows that whereas Class 1 prepositions are true function words equivalent to English Ps, Class 2 prepositions are really noun-like elements. For example, Class 1 prepositions require an object, whereas Class 2 Ps do not (7a, b). Class 2 Ps can occur after determiners and can even bear plural morphology (whose function is apparently intensification) (7c, d), whereas Class 1 prepositions cannot. Finally, only PPs headed by Class 2 prepositions appear in case positions and are joined to nominals by Ezafe; Class 1 prepositions do not (7e, f).

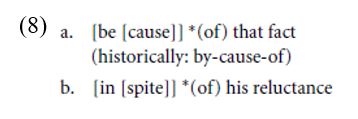

The upshot is that, instead of being a counterexample to the case marker hypothesis, Farsi PPs appear to provide further support for it. It is exactly the noun-like (and presumably [+N]) prepositions that trigger the Ezafe phenomenon – exactly the prepositions that would not be expected to assign case, and whose projections would require it. As a point of comparison with English, we might note that Class 2 prepositions in Farsi appear to resemble complex English Ps like (8a, b), which contain an internal nominal element (cause, spite) and require an internal genitive case-assigner (of).

We find Samiian’s analysis of Ezafe convincing; however, if the analysis is correct, important additional questions arise. Accepting that Ezafe occurs to case-mark complements of non-verbal elements, how do modifiers fit in? For example, even if adjectives, as [+N] categories, are case-bearing elements, why would modifiers need case?

|

|

|

|

حقن الذهب في العين.. تقنية جديدة للحفاظ على البصر ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

علي بابا تطلق نماذج "Qwen" الجديدة في أحدث اختراق صيني لمجال الذكاء الاصطناعي مفتوح المصدر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تنتج أنواعًا مختلفة من النباتات المحلية والمستوردة وتواصل دعمها للمجتمع

|

|

|