10:0:44

10:0:44  2023-04-12

2023-04-12  961

961

Methane big part of 'alarming' rise in planet-warming gases

Methane in the atmosphere had its fourth-highest annual increase in 2022, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported, part of an overall rise in planet-warming greenhouse gases that the agency called "alarming."

Though carbon dioxide typically gets more attention for its role in climate change, scientists are particularly concerned about methane because it traps much more heat—about 87 times more than carbon dioxide on a 20-year timescale.

Methane, a gas emitted from sources including landfills, oil and natural gas systems and livestock, has increased particularly quickly since 2020. Scientists say it shows no sign of slowing despite urgent calls from scientists and policymakers who say time is running out to meet warming limits in the Paris Agreement and avoid the most destructive impacts of climate change.

"The observations collected by NOAA scientists in 2022 show that greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at an alarming pace and will persist in the atmosphere for thousands of years," NOAA Administrator Rick Spinrad said in a statement accompanying the report. "The time is now to address greenhouse gas pollution and to lower human-caused emissions as we continue to build toward a climate-ready nation."

Methane gas leaks from wells and natural gas lines and wafts from manure ponds, decomposing landfills, and directly from livestock.

"Ruminant animal herds like goats, sheep, and cows in particular are one of the largest human-driven sources of methane," said Stephen Porder, a professor of ecology and assistant provost for sustainability at Brown University.

Scientists continue to discover that methane emissions from both the fossil fuels industry and the environment are largely underestimated.

"We are confident that over half of the methane emissions are coming from human activities like oil and gas extraction, agriculture, waste management, and landfills," said Benjamin Poulter, NASA research scientist.

The exact amounts of methane that have come from human activity versus natural environments over the past few years is not currently known, but scientists say that humans have little control over ecosystems that start emitting more methane due to warming.

"If this rapid rise is wetlands and natural systems responding to climate change, then that's very frightening because we can't do much to stop it," said Drew Shindell, Duke University professor and former climate scientist at NASA. "If methane leaks from the fossil fuels sector, then we can make regulations. But we can't make regulations on what swamps do."

Reality Of Islam |

|

People with

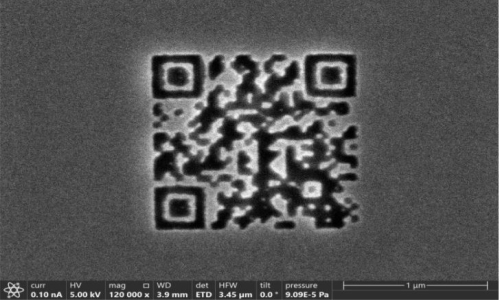

A 1.98-squa

Researchers

A well-know

9:3:43

9:3:43

2018-11-05

2018-11-05

10 benefits of Marriage in Islam

7:5:22

7:5:22

2019-04-08

2019-04-08

benefits of reciting surat yunus, hud &

9:45:7

9:45:7

2018-12-24

2018-12-24

advantages & disadvantages of divorce

11:35:12

11:35:12

2018-06-10

2018-06-10

6:0:51

6:0:51

2018-10-16

2018-10-16

7:6:7

7:6:7

2022-03-21

2022-03-21

2:5:14

2:5:14

2023-01-28

2023-01-28

8:39:51

8:39:51

2022-09-23

2022-09-23

7:26:19

7:26:19

2022-04-08

2022-04-08

9:50:37

9:50:37

2023-02-28

2023-02-28

7:34:7

7:34:7

2023-02-28

2023-02-28

1:16:44

1:16:44

2018-05-14

2018-05-14

5:41:46

5:41:46

2023-03-18

2023-03-18

| LATEST |