x

هدف البحث

بحث في العناوين

بحث في المحتوى

بحث في اسماء الكتب

بحث في اسماء المؤلفين

اختر القسم

موافق

Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

literature

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Specifiers

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

76-3

5-8-2022

1004

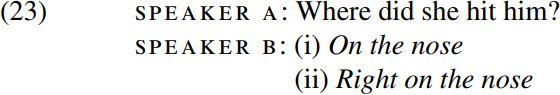

A question which arises from our analysis of tense auxiliaries in (17/22) above as having an immediate projection into T-bar and an extended projection into TP is whether there are other constituents which can have both an intermediate and an extended projection. The answer is ‘Yes’, as we can see by comparing the alternative answers (23i/ii) given by speaker B below:

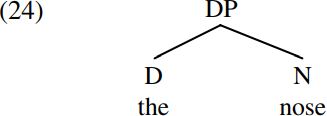

Let’s first look at the structure of reply (i) On the nose in (23B), before turning to consider the structure of reply (ii) Right on the nose. On the nose in (23Bi) is a prepositional phrase/PP derived in the following fashion. The determiner the is merged with the noun nose to form the DP/determiner phrase the nose in (24) below:

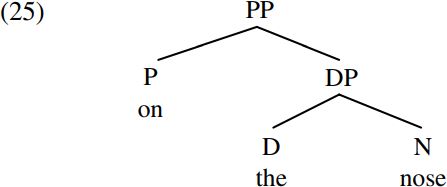

(In work in the 1960s and 1970s, expressions like the nose were taken to have the categorial status of a NP/noun phrase; but here we follow more recent work dating from Abney 1987 which takes them to have the status of a DP/determiner phrase.) The preposition on is then merged with the resulting DP the nose to form the prepositional phrase/PP on the nose, which has the structure (25) below:

The overall expression on the nose is a projection of the preposition on and so has the status of a prepositional phrase: the head of the PP on the nose is the preposition on and the complement of the preposition on is the DP the nose.

Given the traditional assumption that a verb or preposition which takes a noun or pronoun expression as its complement is transitive, on is a transitive preposition in this use, and the nose is its complement.

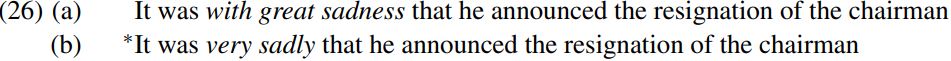

Now consider the structure of reply (ii) Right on the nose in (23B). This differs from the PP on the nose in that it also contains the adverb right. It seems implausible to suppose that the adverb right is the head of the overall expression, since this would mean that right on the nose was an adverbial phrase/ADVP: on the contrary, it seems more plausible to suppose that right on the nose is a prepositional phrase/PP in which the adverb right is a modifier of some kind which serves to extend the prepositional expression on the nose into the even larger prepositional expression right on the nose (so that the head of the structure is once again the preposition on). Some evidence that right on the nose is a PP (and not an ADVP) comes from cleft sentences (i.e. structures of the form ‘It was a car that John bought’, where the italicized constituent a car is said to be focused, and hence to occupy focus position in the cleft sentence structure). As we see from (26) below:

A prepositional phrase/PP like with great sadness can be focused in a cleft sentence, but not an adverbial phrase/ADVP like very sadly. In the light of this observation, consider the sentences below:

A prepositional phrase/PP like with great sadness can be focused in a cleft sentence, but not an adverbial phrase/ADVP like very sadly. In the light of this observation, consider the sentences below:

The fact that both on the nose and right on the nose can occupy focus position in a cleft sentence suggests that both are PP/prepositional phrase constituents: right on the nose cannot be an ADVP/adverbial phrase since we see from (26b) above that adverbial expressions cannot be focused in cleft sentences.

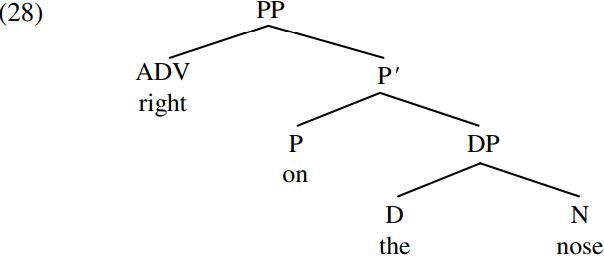

The conclusion we reach from the data in (26)–(27) above is that the adverb right in right on the nose serves to extend the prepositional expression on the nose into the even larger prepositional expression right on the nose. Using the bar notation introduced in (17) above, we can analyze right on the nose in the following terms. The preposition on merges with its DP complement the nose to form the intermediate prepositional projection on the nose which has the categorial status of  (or P-bar, pronounced ‘pee-bar’); the resulting P-bar on the nose is then merged with the adverb right to form the PP below:

(or P-bar, pronounced ‘pee-bar’); the resulting P-bar on the nose is then merged with the adverb right to form the PP below:

In other words, just as a tense auxiliary like are can be projected into a  like are trying to help you by merger with a following VP complement and then further projected into TP by merger with a preceding pronoun subject such as we, so too a preposition like on can be projected into a

like are trying to help you by merger with a following VP complement and then further projected into TP by merger with a preceding pronoun subject such as we, so too a preposition like on can be projected into a  like on the nose by merger with a following DP complement and then further projected into a PP like right on the nose by merger with a preceding adverbial modifier such as right.

like on the nose by merger with a following DP complement and then further projected into a PP like right on the nose by merger with a preceding adverbial modifier such as right.

Although we in (17) serves a different grammatical function from right in (28) (in that we is the subject of are trying to help you, whereas right is a modifier of on the nose), there is a sense in which the two occupy parallel positions within the overall structure containing them: just as we merges with a  to form a TP, so too right merges with a

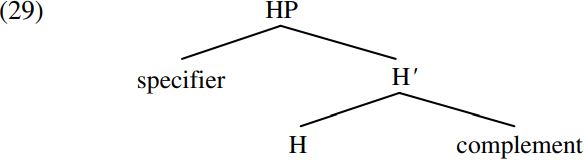

to form a TP, so too right merges with a  to form a PP. Introducing a new technical term at this point, let’s say that we serves as the specifier of the T are, of the T-bar are trying to help you and of the TP we are trying to help you in (17), and that right likewise serves as the specifier of the P on, of the P-bar on the nose and of the PP right on the nose in (28). More generally, we can say that a specifier is an expression which merges with an intermediate projection H-bar (where H-bar is a projection of some head word H) to project it into a maximal projection HP in the manner shown in (29) below:

to form a PP. Introducing a new technical term at this point, let’s say that we serves as the specifier of the T are, of the T-bar are trying to help you and of the TP we are trying to help you in (17), and that right likewise serves as the specifier of the P on, of the P-bar on the nose and of the PP right on the nose in (28). More generally, we can say that a specifier is an expression which merges with an intermediate projection H-bar (where H-bar is a projection of some head word H) to project it into a maximal projection HP in the manner shown in (29) below:

Given the informal word-order rule we suggested earlier (‘Any constituent of a phrase HP which is the sister of the head H is positioned to the right of H, but any other constituent of HP is positioned to the left of H’), it follows that heads precede complements but specifiers precede heads in English: in other words, English is a language with complement-last and specifier-first word order.

The assumption that determiners can head projections of their own also has interesting theoretical implications. We see from (29) above that syntactic heads can typically be merged with both a complement and a specifier. If determiners function as heads, we should expect that they too will allow an appropriate kind of expression to function as their specifier (in an appropriate kind of structure). In this connection, consider the following contrast:

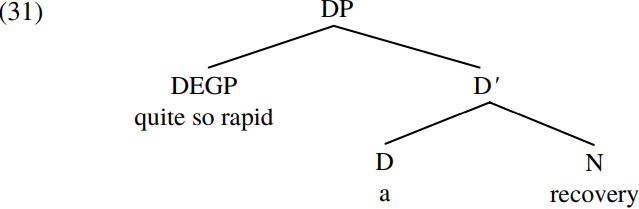

Modifiers in English are typically positioned between a determiner like a and a noun like recovery – and indeed this is the case with the modifying expression quite so rapid in (30a). However, in expressions like quite so rapid which contain a degree word like so/too/how, the whole degree expression can instead be positioned in front of a determiner like a – as in (30b). What syntactic position does the degree expression occupy in such cases? We can give a principled answer to this question if we assume that determiners can project into determiner phrases, since we can then say that a degree expression positioned in front of a determiner occupies spec-DP – i.e. the specifier position within the determiner phrase. On this view, (30b) would have the skeletal structure shown below (where we follow Abney 1987 in taking an expression like quite so rapid to be a projection of the DEG/degree word so, and hence to be a DEGP constituent):

An analysis like (31) would mean that there is symmetry between the structure of determiner phrases and other types of phrase, in that (like other phrases), DPs allow a specifier of an appropriate kind. Indeed, although its internal structure is not shown in (31), the DEGP quite so rapid could be argued to have a similar specifier+ head+ complement structure, with the degree word so serving as its head, the adjective rapid as its complement, and the adverb quite as its specifier.

As those of you familiar with earlier work will have noticed, the kind of structures we are proposing here are very different from those assumed in traditional grammar and in work in linguistics in the 1960s and 1970s. Earlier work implicitly assumed that only items belonging to substantive/lexical categories could project into phrases, not words belonging to functional categories. More specifically, earlier work assumed that there were noun phrases headed by nouns, verb phrases headed by verbs, adjectival phrases headed by adjectives, adverbial phrases headed by adverbs and prepositional phrases headed by prepositions. However, more recent work has argued that not only content words but also function words can project into phrases, so that we have tense phrases headed by a tense-marker, complementizer phrases headed by a complementizer, determiner phrases headed by a determiner – and so on. More generally, the assumption made in work over the last twenty years or so is that in principle all word-level categories can project into phrases. This means that some of the structures we make use of here may seem (at best) rather strange to those of you with a more traditional background, or (at worst) just plain wrong. However, the structure of a given phrase or sentence cannot be determined on the basis of personal prejudice or pedagogical precepts inculcated into you at secondary school, but rather has to be determined on the basis of syntactic evidence of the kind discussed below. I would therefore ask traditionalists to be prepared to be open to new ideas and new analyses (a necessary prerequisite for understanding in any discipline).