Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

أقرأ أيضاً

التاريخ: 2023-11-29

التاريخ: 2023-04-01

التاريخ: 2023-03-25

التاريخ: 2023-03-24

|

A case study of the semantics of clear - The analysis

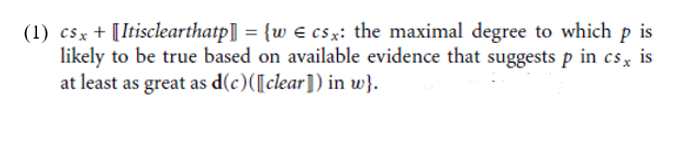

It is easy to model the use of vague predicates in a Stalnakerian model of context update by making the assumption that during a conversation the common ground includes the facts that a conversation is taking place, that the speaker is speaking, the addressee is being addressed, and so on. Incorporating this with the analysis of vague predicates leads to the observation that one way in which the worlds in a context may vary is in the value of the delineation function that is associated with a vague predicate as applied to the version of the conversation in that world. Bearing these assumptions in mind, a first attempt at an analysis of clear is provided in (1).

The analysis in (1) captures the connection between likelihood and clarity, as mediated through a stage of analysis of available evidence. The idea behind this is the observation that for a determination of probability to occur, an experiencer needs to make an evaluation based on available evidence. In this way, the nature and perceived applicability of the nature of available evidence is hard to separate from a determination of the probability of a proposition.

The analysis in (1) also specifies the respect in which asserting clarity is similar to asserting the applicability of a vague predicate. However, it cannot be right. The problem is that in Gunlogson’s model (as well as other Stalnakerian models), propositions don’t have probabilities. For any given possible world, either Briscoe is a detective, or he is not. No matter what the standard for clarity is, worlds in which the probability is 1 will survive update according to (1), and worlds in which the probability is 0 will not. Thus, in the absence of acknowledging probability, the meaning of It is clear that Briscoe is a detective is identical to the meaning of Briscoe is a detective, which has been shown to be incorrect.

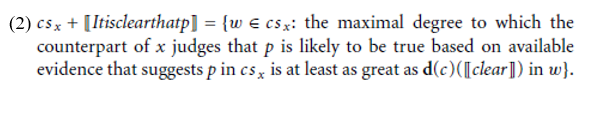

This problem can be solved by building on the observation made above that likelihood is a judgment made by some sentient creature who is contemplating p. Therefore, if likelihood plays a role in assertions of clarity, it is possible to appeal to the judger of likelihood.

In a departure from standard Hintikka-style assumptions about using an equivalence relation to model doxastic accessibility between worlds, with the result that individuals effectively have the same beliefs in all accessible worlds, I follow Barker and Taranto and refine the context change potential in (1) as (2), which considers judgments of likelihood at each world. That is, every possible world in w is evaluated in terms of how likely the counterpart of x considers p to be. The definition in (2) recognizes that belief is a gradient attitude, and behaves just like any other vague predicate.

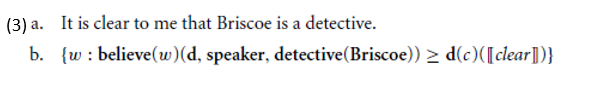

In practical terms, this means that if a speaker asserts (3a) with the semantics in (3b), then only those worlds will survive update at which the speaker believes Briscoe is a detective, based on her determination of likelihood in light of available evidence.

Worlds that are excluded will include worlds in which there is enough uncertainty (or not enough certainty) to reduce the speaker’s belief in Briscoe’s status as a detective to below that world’s specified threshold for clarity. Worlds may survive in which Briscoe is not a detective, as long as the speaker believes that Briscoe is a detective in that world.

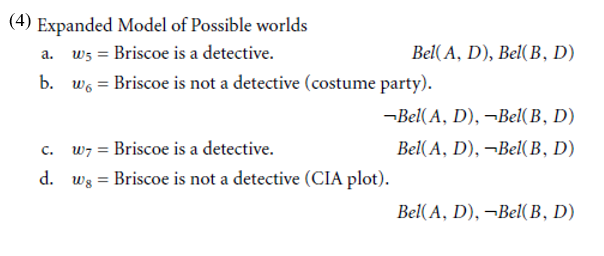

An example is provided in (5), based on the states-of-affairs modeled in (4). The model includes information about Briscoe’s being a detective, as well as information about the clarity of this proposition in terms of the discourse participants’ beliefs. In (4), D abbreviates the proposition expressed by Briscoe is a detective and Bel is a belief operator used to indicate whether A or B believes that Briscoe is a detective. In (4), w5 is a world in which both A and B believe Briscoe is a detective, andw6 is a world in which neither A nor B believes that Briscoe is a detective. In these worlds, the discourse participants’ beliefs happen to align with the facts in the world. In w7, however, only A’s beliefs align with truth in the world. A believes that Briscoe is a detective, which happens to be true, while B does not believe that Briscoe is a detective.

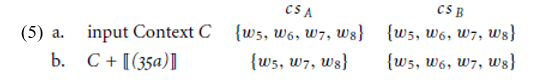

Imagine a situation in which the speaker A is unaware of the CIA plot; her utterance of (3a) is modeled in (5). The input context is modeled in (5a), and the result of her utterance eliminates w6, the world in which A does not believe that Briscoe is a detective, fromher commitment set. Her commitment set still includes w8, a world in which Briscoe isn’t a detective, but because in this world there is sufficient evidence to persuade our speaker that Briscoe is a detective, this world remains a live possibility.

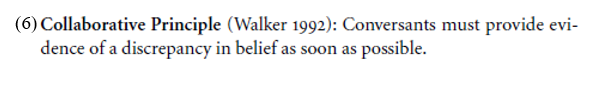

In a departure from Gunlogson (which will be addressed below), the analysis of clear presented here adoptsWalker’s Collaborative Principle.

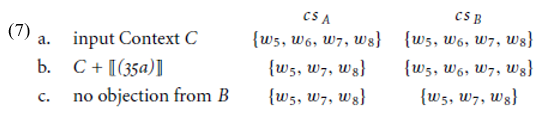

The claim made here about the semantics of clear is that in the normal course of events, when A utters It is clear to me that Briscoe is a detective, B will have no choice but to accept the fact that it is clear to A – A is the highest authority on A’s beliefs. By bringing in Walker’s Collaborative Principle, it is possible to formalize what happens if B does not immediately express doubt about the truth or sincerity of A’s statement. If B remains silent, then the discourse model will reflect individual public commitments on the part of both A and B to A’s belief in Briscoe’s being a detective. Thus, the representation of B’s commitment set as depicted in (5b) is incomplete. B’s commitment set must also reflect her belief (or acquiescence) in A’s commitment to the clarity of the proposition expressed by Briscoe is a detective, as shown in (7).

The commitment set of B in (7c) includes two worlds in which it is not clear to B that Briscoe is a detective. Her commitment set includes w7 and w8, worlds in which it is clear to A that Briscoe is a detective, even though it is not clear to B that Briscoe is a detective. Comparison of the commitment sets of A and B in (7c) shows that synchronization has happened. While there is not agreement about whether or not Briscoe is a detective, the information states of A and B are the same, and they reflect the mutual understanding that A believes that B is a detective, but B does not.

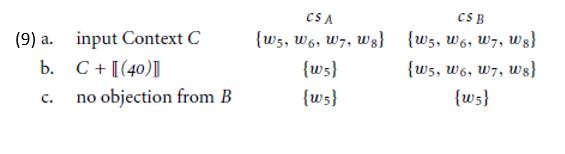

Example (9) shows the update effect of the assertion of simple clarity expressed in (8).

Since the semantics of clear specify that the default interpretation of the experiencer is as the discourse participants, the only world that survives update is w5, the sole world in which it is clear to both A and B that Briscoe is a detective. Since B makes no objection, the Collaborative Principle licenses an update to B’s commitment set as well, showing that all discourse participants are committed to p for the sake of the conversation.1 From a practical standpoint, B may allow this to happen in a situation in which she does not yet believe that Briscoe is a detective, but she does not have evidence suggesting that he is not. By accepting an utterance of It is clear that Briscoe is a detective, she allows into the common ground a version of the proposition expressed by Briscoe is a detective in a way that suggests the proposition may be subject to reevaluation in terms of its truth.

By the analysis, dialogues involving the denial of simple assertions involve contradiction and repair, while denials of assertions of personal clarity do not. Consider (10).

Here, B’s statement contradicts A’s statement. Presumably, some form of repair must occur before the conversation can proceed. In contrast, the dialogue in (11) includes A’s assertion of personal clarity.

In (11), B has not contradicted A: it remains true that it was clear to A that Briscoe was a detective. Further discussion between A and B might reveal that they disagree on the minimum standard for clarity, that the speaker and hearer do not have access to the same evidence in support of the proposition that Briscoe is a detective, or that they disagree about what evidence is suggestive of the truth of this proposition. Functionally, an utterance of (11) opens the conversation up to continued discussion that might result in synchronizing the beliefs of A and B. Whether or not A will continue to believe that Briscoe is a detective will depend on her belief in the validity of B’s statement and how that relates to the likelihood of Briscoe’s being a detective.

1 As an anonymous reviewer has suggested, it may be the case that the discourse participants are committed to more than p – they are committed to not considering revising their assumptions about p for the foreseeable future.

|

|

|

|

لشعر لامع وكثيف وصحي.. وصفة تكشف "سرا آسيويا" قديما

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

كيفية الحفاظ على فرامل السيارة لضمان الأمان المثالي

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تجري القرعة الخاصة بأداء مناسك الحج لمنتسبيها

|

|

|