تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Aberration

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 34

2024-03-28

1472

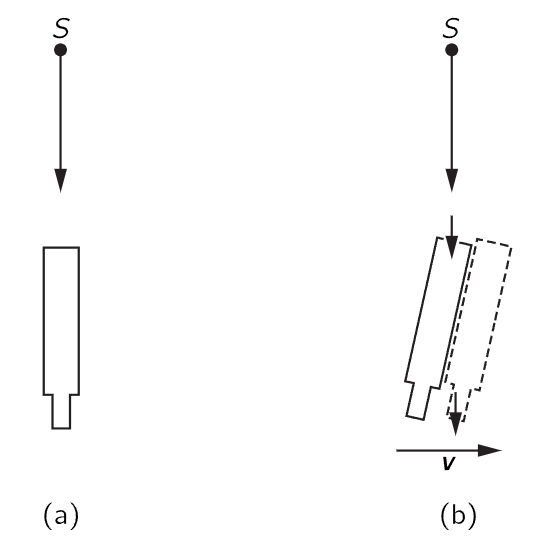

Fig. 34–12. A distant source S is viewed by (a) a stationary telescope, and (b) a laterally moving telescope.

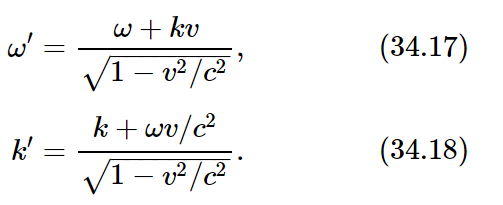

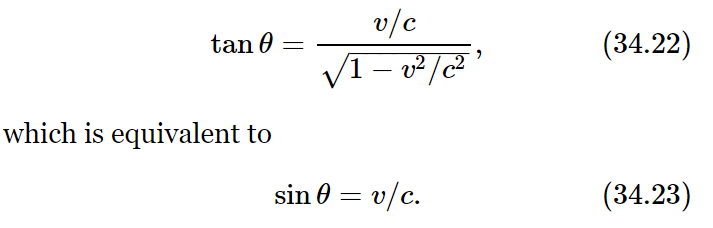

In deriving Eqs. (34.17) and (34.18), we have taken a simple example where k happened to be in a direction of motion, but of course we can generalize it to other cases also. For example, suppose there is a source sending out light in a certain direction from the point of view of a man at rest, but we are moving along on the earth, say (Fig. 34–12). From which direction does the light appear to come? To find out, we will have to write down the four components of kμ and apply the Lorentz transformation. The answer, however, can be found by the following argument: we have to point our telescope at an angle to see the light. Why? Because light is coming down at the speed c, and we are moving sidewise at the speed v, so the telescope has to be tilted forward so that as the light comes down it goes “straight” down the tube. It is very easy to see that the horizontal distance is vt when the vertical distance is ct, and therefore, if θ′ is the angle of tilt, tanθ′=v/c. How nice! How nice, indeed—except for one little thing: θ′ is not the angle at which we would have to set the telescope relative to the earth, because we made our analysis from the point of view of a “fixed” observer. When we said the horizontal distance is vt, the man on the earth would have found a different distance, since he measured with a “squashed” ruler. It turns out that, because of that contraction effect,

It will be instructive for the student to derive this result, using the Lorentz transformation.

This effect, that a telescope has to be tilted, is called aberration, and it has been observed. How can we observe it? Who can say where a given star should be? Suppose we do have to look in the wrong direction to see a star; how do we know it is the wrong direction? Because the earth goes around the sun. Today we have to point the telescope one way; six months later we have to tilt the telescope the other way. That is how we can tell that there is such an effect.

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاب (سر الرضا) ضمن سلسلة (نمط الحياة)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاب (سر الرضا) ضمن سلسلة (نمط الحياة)