Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-12

Date: 7-3-2022

Date: 2025-04-23

|

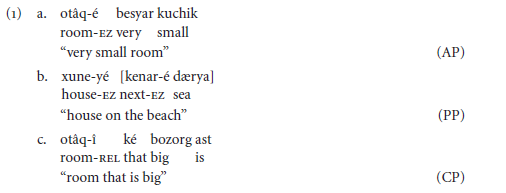

Ezafe and the deep position on nominal modifiers Introduction

In languages exhibiting the Ezafe construction, such asModern Persian, nominal modifiers generally follow the noun, and a large class of nominal modifiers, including APs, NPs, some PPs, but not relative clauses, require a “linking” element, referred to as Ezafe. Thus in (1a), the noun otâq ‘room’ is modified by the adjective phrase besyar kuchik ‘very small.’ The Ezafe vowel é appears in between, suffixed to the noun. In (1b), the noun xune ‘house’ is followed by a restrictive PP, kenar-é dærya ‘on the beach.’ The two are connected by Ezafe, which also appears internally, between the preposition and its object. Finally (1c) shows the noun otâq modified by the relative clause î- ké bozorg ast ‘that is big.’ No Ezafe appears in this case; the relative clause initial -î is a distinct morpheme.1

The Ezafe construction raises a number of interesting questions, not the least of which is: What is the Ezafe morpheme? What is its status under current grammatical theory?

In this chapter we develop a proposal advanced by Samiian (1994) that Ezafe is a case-marker, inserted to case-license [+N] elements. After introducing Ezafe, and reviewing Samiian’s arguments for its case-marker status, we go on to consider two simple questions that arise from her results:

_ Why do modifiers require Case?

_ What is their Case-assigner?

Case-marking (as opposed to agreement) is typically associated with argument status; however, the Ezafe-marked items in (1a) and (1b) are modifiers. Why would modifiers need case? We suggest an answer to these questions based on an articulated “shell structure” for DP proposed by Larson (2000c). Under this account, (most) nominal modifiers originate as arguments of D, a view defended in classical transformational grammar by Smith (1964), and in generalized quantifier theory by Keenan and Stavi (1994). We also relate our account to other cases of postnominal APs, including English indefinite pronoun constructions and the Greek “poly-definiteness” construction, and to adjectival inflection in Japanese, following Yamakido (2005, 2007). If correct, our conclusions suggest a return to the early transformationalist view of nominal modifiers as complements of the determiner that originate in the position of relative clauses.

1 All data in this paper are drawn from either Samiian (1994) or Ghozati (2000).

|

|

|

|

حقن الذهب في العين.. تقنية جديدة للحفاظ على البصر ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"عراب الذكاء الاصطناعي" يثير القلق برؤيته حول سيطرة التكنولوجيا على البشرية ؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جمعية العميد تعقد اجتماعها الأسبوعي لمناقشة مشاريعها البحثية والعلمية المستقبلية

|

|

|